“If you want to learn how to fight properly and effectively with the long sword, so that you may, without gloves and without all armour, guard your hands and your entire body against all kinds of weapons, against sword, against spear, against halberd, against long knife and also against other weapons, then firstly mark that you know well the strikes and the steps, and mark that you always turn your hands upward with the hilt, and always hide behind the sword, and hold the head close to the hilt…”

-Hugo Wittenwiler, ca 1493

The starting point

This time I will start with stating outright that this article is much based on my own personal experience in trying to understand and learn historical fencing. However, having talked about these topics many times with quite a few people over the last few years I know that there are many who share similar experiences and issues in their own fencing. Please, keep in mind that none of what I express here is criticism against other people or their ambitions. I am just trying to understand these issues, the cause for them and what the implications are.

To begin with it would probably be best if I try to describe my personal ambition in studying HEMA. The actual fighting and training thereof is only part of the satisfaction I get out of HEMA and while I certainly enjoy the fighting, it is not my only drive. Instead I wish to, as much as possible in our modern day, understand what the masters of old are trying to teach us, to understand how the fighting arts were performed with regards to techniques, tactics, strategics, limitations based on practical realities with regards to concepts of honour, manliness, fairness, practicality and so on. So, I am not just in it to fight. I aim to learn to fight in a quite specific way, which is of course also what the majority of the HEMA community does too.

To me, we have still just taken a few steps on a quite long road to understanding all of this and I believe we have quite a long distance to go yet, which is why it is so important that we keep focus on the goal in the distance, and don’t allow us to get distracted, misled or over-confident on the way. Not everyone has the same emphasis on actual historical fencing, instead just enjoying the opportunity to fight with steel, and I realize that, but to me all of it is incredibly important as we claim to study Historical European Martial Arts. Each of those words are equally important, in my eyes.

Our interpretations and theories of course have to be tested against a properly resisting opponent, occassionally stepping out of our comfort zone for a reality check, which can be done in different contexts; free fencing without protection, sparring with required protection or through competition, facing unknown opponents. A very important question however, is what defines a “properly resisting” opponent. This is one of the things this essay tries to elaborate on, as I believe it is much more complex than just physically resisting each other’s actions and very much a question of having a certain mindset.

One of the most important aspects to research other than just reading the instructions in the treatises, is to study the context in which they were written and designed for. For this reason we need to study all aspects of the medieval and Renaissance society, ranging from, but not limited to, construction of clothing, arms & armour to sociology, politics, history, geometry and philosophy/religon/mysticism. Without an understanding of the context, I strongly believe we will never truly understand the treatises and our results will be flawed due to too much modern influence.

Rebooting our minds

Stronger and stronger I think we on the whole need a bit of a reboot in how we approach the fencing and our training, if we are to ever understand the fencing treatises we study. The tournaments is a seemingly always controversial topic that is related to all of this, but although I personally believe many of us get into them far too early, I also understand the belief that it is the best way of pressure testing interpretations. However, I suspect that we commonly enter all this, and not just the tournaments but all our training, with an often lacking attitude and consequently, the tournaments will not quite work as hoped, in many cases. I will try to explain why I belive this is so.

One of the chief causes, I believe, is due to the fact that we practice with a lot of protective gear and as this is increasing, as the tournaments get more and more aggressive, and more hard-hitting than I think was originally taught for sword fencing, I also fear that it will lead us astray unless we figure out how to remedy it. The gear in itself isn’t the problem and we certainly need it, but the resulting mindset is, I think, as we tend to trust in it to keep us safe, when it really should be our skill and our weapons that do so. We know that those we study practiced with rather little protection and I believe that changed their whole mentality into a much more careful, more focused and in some respects less aggressive fencing style, which also allowed them to practice a more technical fencing, something which in some respects is difficult for us to do with equipment that sometimes even hinder us when applying certain historical techniques.

Fighting modes

The different modes of a fight depend on both the weapons used and the style, but basically any fight can have three different types of exchanges and this relates to, in German terms, the handling of the Vor and Nach. Either you are just defending, parrying, or the opposite, your opponent is doing nothing but parrying. In between there is a middle distance fight, where you toss the Vor back and forth between you. This can mean that you strike-parry, strike-parry in many exchanges (often we see Zornhaw-Schrankhut/Hengetort-parries).

This, and just defending I think we often focus too little on in our training, but you see it in for instance, Jogo do Pau, and you quickly recognize this when you fence without protection too. Somehow, Jogo do Pau fencers naturally know when to just strike and then be ready to defend versus striking and then do another attack as the opponent leaves a small gap.

Personally, I too often don’t wait for a gap, but just continue with whatever plan I have in my head. Perhaps this is a result of not quite understanding how to apply the advice given in the older treatises, about not caring about the opponent or his sword, instead having a plan in our heads and cutting straight to the body. Another big part of it is most likely that the defender doesn’t truly feel threatened by the attack and therefore instead tries to directly counter with a displacing cut, ie a Maisterhauw, something which is ideal, but not what you should always do.

It may also be that the advise in the early treatises works the best against fencers who aren’t trained in the Liechtenauer tradition, like when these treatises were written, but not as well in Meyer’s time, or ours, as everyone tries to use the same aggressive, Vor/Meisterhauw approach, having studied Liechtenauer and his disciples. This may well be a crucial difference that we would do well in considering, I believe.

The myth of the Unconquerable Chuck

Depending on how we read the sources we can put focus on different aspects of the texts. For example, some parts teach us the importance of switching between cutting, thrusting and slicing, while other parts focus on cutting continuously. Such seeming contradictions combined with a bit of a sterotypical image of the hero and top fighters as being completely over-whelming and undefeatable, crushing their enemies like a tank, perhaps affect our reading, leading to a slight shift in our understanding of what the masters were trying to teach us.

Yes, both the early and late “German” treatises tell us to be dominant, to take the first initiative, but they also tell us about the importance of control, of the bind. So, when we are told to disregard the opponent’s weapon and his intentions, that might not be meant as literally as we could think. It just relies on the notion that the defender will first focus on staying safe with a parry, rather than counter-attacking.

No fighter is forever undefeatable and no combat system can be based around such a notion. For example, reading Meyer, it is quite clear that he was aware of this. This is why he focuses on the Abzug, the withdrawal, something you need to know how to handle when things don’t end up quite as planned. And yet many of us struggle to learn the perfect Vorschlag, the single blow that will end the fight instantly.

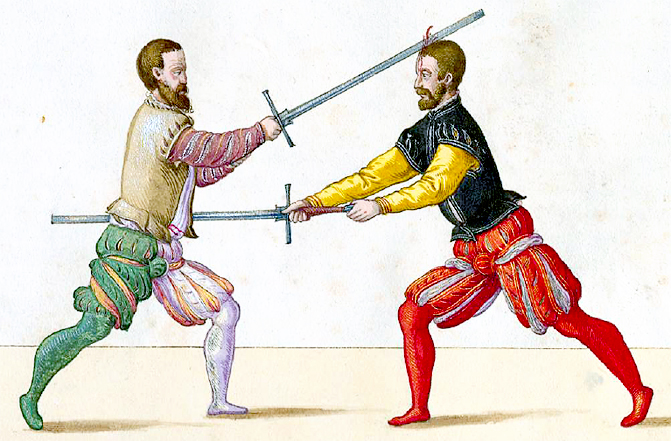

Judicial duelling in mid 14th cent Sweden. Notice the many injuries on both parties.

This I think is a dangerous idea that is based on a bit of a misunderstanding of the sources, causing us to try to apply this at all times, instead of only as the opportunity arises. Yes, a few fighters can pull it off consistently, but I don’t believe it is what the masters are teaching us. Instead, I believe even the Liechtenauer lineage is focused on fencing safely. This is why the old terms for fencing masters were Schirmmeister, Maitre d’Escrime and Maister of Defense, all terms focusing on defense rather than offense. Taking initiative is certainly part of staying safe, but control is much more important. And despite this many of us are much more concerned with hitting the other guy than protecting ourselves.

Control then, can be worked with in two ways, which both relate to handling of distance, and flow. First of all, you can try to remain in the bind, without striking, and instead moving to slice or thrust. Second, you can strike around into another stance for a static parry or a Versetzen, a displacing cut. This creates a natural flow of exchanges where for the outside viewer it is hard to tell who is actually in Vor and who is in Nach. It is a matter of a fraction of a second that separates the two, and both fencers are actually doing the same actions, trying to outtime each other.

Focus, at all times is on not attacking properly without sensing an opportunity to do so, and if there is no space, instead just parry, preferably with a threat keeping the point at the opponent. I think this is what Meyer speaks of when he tells us ‘Thus you shall now go in all devices from the sword to the body, and from the body to the sword‘, which mustn’t be confused with foolishly chasing the sword. I think it is also part of his long vs short cuts, where the latter are more defensive and the former more offensive.

Working with a new mindset

The problem however, when we try to work with such an approach, is that many of us already have something else ingrained into all our training, and as a consequence we often blindly go for the hits, ending up with double-hits, instead of constantly keeping safe and just going for the attack when there is enough room for it. This is something I just started working on with some friends, and it is quite difficult changing our mindsets, and especially bringing it into our sparring, especially if one fighter doesn’t have that mentality, and acts overly aggressive and suicidal (something which certainly happens in real life situations also, often with nasty endings for both parties).

This is very important to understand as this is at the very core of what makes modern tournaments somewhat problematic. We all need to foster the same mentality if they are to properly work as a tool for understanding the Art. A different mentality may well mean that you can place well in any tournament, but it may also easily lead you away from the historical fencing, based in real combat, towards something else. Simply put; It is “easy” being suicidal and not caring about your own personal safety in a safe environment, but it doesn’t teach you historical fencing properly. For this reason, tournament success isn’t necessarily a good measurement of a good historical fencer, although it can be.

These issues with different mindsets I think we see quite often in the tournaments. The ruleset, be they history-based or modern, may well be good and fair, but if the mindset is wrong, then it doesn’t necessarily work so well, regardless of the rules we use. The change needs to go much deeper. It is not just a matter of quickly changing our minds and thinking; now I am going to fight like this is a real sword. I think it needs to be meshed into all our training, into the very fabric of what we do. And that change, I think, will take quite some time. Of course, many of the best fighters have figured this out already and it is what makes them successful, regardless of what tournament they enter. So, I am more speaking of myself and people who find themselves having similar issues.

Rules and martiality

A question that often comes up when debating tournaments is that they by nature will distort the art as the real fighting arts was without rules and thus tournaments will always only be “sport”. However, I believe this is a bit of a delusion as we all train with rules that restrict what we do. Very, very few actually allow striking full power mortschlag, eye gouging, crushing of testicles etc. Training maiming and killing techniques safely doesn’t necessarily put us closer to understanding the Art, although I too belive it is important, even necessary to train them if we are to fully understand the art.

However, no matter how we approach the training, we will never get near an actual combat situation, unless we are prepared to take considerably more risks in training. But we can approach both our training and the tournaments in a way that puts us closer. The tournaments are an important part of the martial art and it has pretty much always been so, both in ancient times and during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Much of the Art actually comes from such situations I think. It is just the other side of the coin and it was considered, it appears, to be quite important to the shaping of the “German” martial society, with tournaments taking place basically every weekend in some cities. Just imagine that; men fighting until first blood with steel and wooden dussacken, every damn week. That breeds some really tough bastards, I think. Very few train in a way that even approximates that, despite bold words about sticking to the true Art and claiming that tournaments inevitably corrupts the art.

Yes, regulating the Art with fighting in tournaments changes how you apply it, but not necessarily in a bad way. It doesn’t necessarily mean that you loose all “martiality” in doing this. It just forces you to show more bravado and skill. At least that is how I believe it was back in the day. Furthermore, even war has rules and it has pretty much always been so. Certain things have been considered dishonourable and cowardly, especially against your countrymen, like Germans or Englishmen not thrusting at each other. On the other hand, quite brutal actions are also done for very logical reasons, and even more so against people from cultures that are different from your own, like during the crusades or in the clashes between the Habsburgers and the Ottoman Empire. None of this is contradictory though.

However, rules don’t solve everything and no ruleset will ever be perfect without the correct mindset. Like Mike Cartier of the MFFG suggested some time ago, we also need to practice blossfechten and other things to change our basic mindset.

From the “Goliath” Treatise of ca 1510-20.

So perhaps we shouldn’t all simultanously rush to join the tournaments? They are quickly becoming very professional, with really expensive prizes and while that has its value, I also think at this stage there are strong risks that it will lead to negative results if we aren’t very careful, as most of us simply aren’t ready for this. There is a small group of fighters that are, but the ones that are the best are really only the ones who are ready to enter the tournaments, from a historical point of view, that is.

A few years ago in a big tournament, about 20% went to the emergency, commonly with hand injuries resulting from parrying with their hands and I think this reveals a rather serious problem in both training and attitude. Just imagine if we had all entered these tournaments without protection… It would be a bloodbath, with real maiming and death in much larger numbers than back in the day.

Possibly we are getting a bit over-confident and perhaps a bit impatient and restless too, as we try to find a different path than that of the slow-progressing teaching methods of Asian Martial Arts. The protection we now wear allow us to strike freely, with great power, but although that may seem like a positive thing, most of us really have no idea what kind of power would be necessary or useful in a real sword fight with sharps. Often, I believe, we forget that our swords are meant to be handled as what they are; really long and sharp kitchen knives, something which would be quite scary on both ends of the sword. The amount of power needed to cut into flesh isn’t really that big and on the other hand, cutting through bone or even contemporary cloth can be futile unless you use proper technique rather than power. This is what I think we see in the treatises, when we see the delicate grippings of swords and cutting deep with almost the middle of the blade.

Learning how to handle a sword properly takes time. And perhaps we should reconsider what the best progression for truly learning this is?

So what path should we take?

Well the historical solutions were simple: The Fechtschulen. And fencing without protection, both inevitably forces you to a certain mentality. So, perhaps fechtschul rules combined with blossfechten with a minimum of protection and other tools, can aid us in understanding all this better? But for this to happen and gain broader acceptance, understanding the fechtschulen and its role in the medieval and Renaissance society is very important, I think.

Thinking of these events as just sport is a mistake, I believe. It was not so much “Sunday fencing” for fun, as it was preparing for combat in a rather brutal way; fencing with steel and wood, without protection and drawing blood regularly while doing so. What this really means is very hard for us to understand without having a living tradition to study or participate in. The whole society was very militaristic at all levels. Comparing to today it would be as if all households owned guns and about 50-60% of them owning machine guns, with 5-10% even owning bulletproof vests. In these households most men were trained in using it all, with many practicing hand-to-hand combat until first blood every week. Their world was much like the Syria, Ex-Yugoslavia, Israel, Somalia, Mali, Rwanda or Iraq of today, only with the fighting extended into a form of Art, displayed regularly for the enjoyment and spirit boosting of the fellow towns people.

Fechtschulen doesn’t emulate actual combat, but I strongly believe it trained for it. Studying Meyer, I sincerely believe he is one of the few masters who actually focuses more on the battlefield, which the really early masters rarely do. Meyer bridges the gap between them and those that soon would focus on teaching troop drills for the cannon fodder, like de Gheyn, Wallhausen etc . He is standing at the crossroads, defending the old ways in quickly changing times.

We should also keep in mind that there were plenty of opportunities to end up in actual combat in the Renaissance and this was the place to train and prepare for most men. Many ended up serving as Landsknechten/Reißläufer, in town militias, as city guards, as body guards etc. And the crime rate involving violence was some 15,000 times higher than that of today. Adding to this, students, which were common in the Freyfechter, lived under church law which meant they couldn’t be prosecuted under local Town Law. This regularly led to some very ugly and lethal fights between students and burghers, not least since the students, unlike regular burghers, were allowed to carry arms in public.

Many towns actually required all burghers to serve in the militias and town guards and in times of military conflict, which was basically the norm of the time, all guilds had to provide with a certain number of members to step outside of the city walls to defend it. This often numbered to about 10% of the burghers. About 80-90% of the taxes were spent on military expenses and all stratas of society had to take part. This is all part of the context of the fechtschulen.

The fechtschulen had restrictions, but my belief is that this was in order to keep these quite brutal tournaments reasonably “safe” and not completely safe, at a level that is quite different to what we do today. Keep in mind that quite a few people got badly injured and even death occured in not too few incidents. So, entering these “sport” events required a mindset not to dissimilar to entering an actual fight. Still, these were “friendly” bouts and I think part of the whole reason behind the guilds was to safeguard that everyone had similar training and entered the tournaments with a similar mindset, thus keeping the levels of serious injury down.

Another aspect of the fechtschul is the show aspect, much like the Roman gladiatorial games or the medieval judicial dueling, both public spectacles which not necessarily ended up in death for the loser. This is often regarded as something negative, but I think this is part of where it becomes an Art. Limiting targets and actions is not necessarily a bad thing, as it forces you to not just work with the easy targets, but also to go for more difficult ones. This, I believe, with time will make you a better swordsman. Anyone can go for the easy targets, like the hands or use the Gheysler, striking with one hand at the legs, but keeping the hands safe while never, even by mistake, cutting the opponent’s hands, requires a specific set of skills, just like having only the head as target.

How do we understand this different mentality then?

Well, this is of course quite hard as we live in a very different society. Interestingly, in Trinidad & Tobago, fighting events quite reminiscent of the fechschulen are still held, events with roots going back to at least the 17th century.

Stick fighting on Dominican Islands, 1770, by Agostino Brunias

Like the fechtschul these Calinda Stick Fights is about showing skill and bravery. You win by causing the opponent to bleed from his head. Thrusting is not used and hands are not targeted, but of course often get hit anyways. Grappling is not allowed, but you are allowed to control the opponent’s arms. Grabbing the opponent’s weapon is also prohibited and you shouldn’t strike an opponent who falls or looses his weapon, although that happens sometimes.

All this is very similar to the fechtschul and particularly the dussack fencing, where contemporary reports speak of people getting severely bruised, but sometimes the fighting has to be halted as people get too bruised without actually bleeding.

Often this is done together with a carneval, again very similar to the Fechtschul and the Schwerttanz performed to celebrate Spring. One source mentions that this started in Trinidad in the late 17th century. The fights are also preceded by the fighters taunting each other, similarly to the fechtschul poems. Traditionally some fighters used to wear carnival costumes, reminiscent of the Kloppfechter, but that appears to be less common today.

Oneil Odel, winner of the 2012 National Calinda Bois fighting in Mayaro.

A cap or a turban is allowed, but most don’t wear it. Blood drawn from any part of the body above the waist will stop the fight, but usually judges have to make the decision as often no real damaging blow is landed within those five minutes. Serious Old-Time Trinidad stick fighters are not very happy with how the contemporary public contests are held, as they think the quality of fighters aren’t very good and in their opinion too few actually know the Art.

Back in the 50-60’s it was quite different. No national rules and fighting took the time it took to get the other guy to bleed. No judges were needed as blood was a clear marker of who had lost. Personally, I find it very interesting to study these clips, the fighters and the mentality they appear to carry. I think there are some important lessons to learn from these and similar clips, as we approach the source material and try to apply it in training and tournament fighting.

Conclusion

Now I am not suggesting that we should all drop all our protective gear and start fencing with bare heads and hands with steel. Most of us are simply not ready for that, so that would just be irresponsible and too dangerous. But there are a variety of things we can do, with variation for different types of weapons like dagger, stick, dussack, longsword, rapier and staff etc. Things like:

- Technique training with eye and mouth protection only.

- Sparring with wood or synthetics and miminal protection of gloves and mask.

- Sparring with steel and miminal protection of gloves and mask.

- Flow exercises with no or minimal protection, with or without footwork.

- Controlled fencing where you put up threats that the opponent has to respond to, rather than trying to hit with full power, so that you can always halt your attack if he/she isn’t responding correctly.

- Sparring with eye and mouth protection only.

- Sparring with restricted targets, e.g. only the head counts and hitting the oppontent’s hands or face means you lose, as does parrying with them.

- Sparring with instant-kill targets, e.g. hitting the head, neck or hands or thrusting to the same or the torso are counted as instant kills.

These are just some suggestions, and I am sure you can come up with many more on your own. Keep in mind that you need to know your weapon well first and that some exercise forms suit different levels and weapons better. So choose wisely. The point is to breed a deeper respect, out of fear, for what we are actually doing here, something which comes quite naturally when you actually physically fear getting hit.

Very good article, congratulations.

“Simply put; It is “easy” being suicidal and not caring about your own personal safety in a safe environment, but it doesn’t teach you historical fencing properly”

From the concept of this phrase I base all my teaching from years.

I divide practice in 3 parts:

1) Controlled teaching: students try technic, slow, or at medium speed when it is learned, without protections, with no “touch”; they understand what happen on their skin.

2) Controlled sparring: students try the same technic, at high speed. Medium protections required.

3) Free sparring: All techincs possible, at all speeds; good protections required.

Congratulations again for your complete exposition of your concept.

Totally agree – this has been my experience of the last two years of competitions at SWASH

Roger, this is a well written article on an important topic. Many people share this point of view. I must admit, my friend, that I have some concerns. Allow me to respectfully present them…

Does safety gear reduce fear and make people less concerned about their defense? Yes! You have identified a real problem. Improvements in safety gear are in many cases encouraging people to be even less concerned about their own defense, causing an escalation of offense and perhaps moving us away from the “true fight”, however we may imagine it. It certainly allows us to be sloppier with our techniques without paying a price.

If we reduce safety gear, will fear make people more concerned for their defense? Yes! Was sehrt, das lehrt. But is this the ONLY way, or even the best way to make people more concerned about their own defense? I would argue “no”.

Is this the only way? > I don’t believe so. This issue can be addressed with carefully tailored training applied over a long period of time. But I grant that not all students will have the time and discipline to accomplish this.

Is this the best way? > I don’t believe so. For several reasons…

The risk/reward ratio is too high. For most, sword fighting is a hobby and not something needed to survive in real-world life and death struggles. We must go home to our families and our keyboards which are rightfully our priority, and unnecessary injuries can interfere with that. Reducing safety gear will encourage people to fight in a safer and more controlled manner, no doubt. But accidents are more likely to cause greater damage when using reduced safety gear. And accidents can happen even to the best and most controlled among us. Please note that accidents are not always caused by reckless disregard for one’s own safety. Miscommunication, weapon breaks, simultaneous actions etc can all cause injuries even to the most controlled of fencers. Safety gear is the last line of defense against accidents.

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, I have serious doubts that bouting with less safety gear will actually make me better prepared for an actual duel. In some ways it can hinder me…

Proscribed targeting, while an interesting exercise in which things can be learned, moves us away from the historical advice to seek the nearest target.

Less gear means fencing with less speed and power. Again, things can be learned from this, but it also introduces problems. It can give the fencers a false sense of what will and will not work at full speed and power. For example, some techniques require the application of the strong part of my sword on the weak part of my opponent’s sword. However, if my opponent is not applying full power my technique may work even if I was sloppy and didn’t get my strong on his weak.

And lastly, while fencing with less safety gear may encourage more awareness of my defense, it also encourages more concern for my opponent’s safety. Obviously I am not going to go after someone who is unprotected with full intent, meaning they will be hurt if they don’t block something I throw at them. In short, I have to pull my punches a lot more than if my opponent was wearing safety gear. It takes a window of space to decelerate a sword. If my opponent is wearing safety gear I can afford to narrow that space and let the gear absorb some of that energy. If my opponent has an unprotected head I either need to be swinging slower to begin with, or I must begin that deceleration from further away. In any case, my lack of commitment to actually hitting his head has a profound affect on his counters, making it easier for him to defend with poorer form.

So in summary, I believe that fencing with less safety gear may solve some problems but introduces other problems of greater weight. Fortunately, disregard of personal safety is an issue that can addressed through other means, such as focused training. In any case, I am very pleased that such a respected figure as yourself is shining a light on this problem within the HEMA community. We simply must get better at defending ourselves!

Shay my friend! Thanks for writing such an extensive reply to this essay! However, I feel that you are missing several points I am making, which is quite understandable since I say many things here which I for practical reasons couldn’t expand as much on.

I am not suggesting that everyone should instantly drop all their protective gear or that everyone should train exactly the same way with a limited amount of approaches. I am just pointing to that we need to be more concerned with our own physical integrity in our fencing and figure out ways to trigger such behaviour.

I don’t think that can be effectively done in artificial ways. I think a certain amount of pain and fear is actually required. The body can take a surprising amount of beating without serious injury and this has been proven many times both outside and even inside of HEMA, and as can be seen in the clips provided here. Many clubs have sparred quite hard in minimal protection of just gloves, mask and elbow protection, and yes we get bruised quite a bit, and it hurts, but it teaches also. Bruises like this certainly causes you to respond a bit, but it leaves nothing serious. And note that this is not some form of machismo etc. It is about learning in a way that is more similar to how people trained historically. http://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=324181080946488&set=a.324180594279870.80520.304263799604883&type=3&theater

However pain isn’t the only factor, since you learn to live with that too. Actual fear and learning to handle it and respecting the weapon, the opponent and the dangers in what we do is more important. And here tournaments, especially at the top levels do have a lot of merit, as getting hit when the stakes are very high causes a similar fear, although it also relates quite a bit to what counts as hits in the rule sets used.

The “full power” level you mention is an interesting topic and I actually talk about it briefly in the text. I sincerely do think you can strike hard enough with wasters and blunts against minimal protection. Hard enough to equate with what would be needed with sharps. In fact, I think we often strike TOO hard with all the protective gear, which sometimes effects the techniques in a negative way. So what is “full power” really? Is it really striking as hard as possible, or could it be as hard as is required? There is reason to believe that the latter is something we should think more about, as striking at bone and cloth isn’t quite as effective as many think and vice versa, cutting meat, is quite easy, not to mention thrusting.

Keep in mind that the people we learn from learned all this of necessity and while they certainly could have worn head and hand protection, it seems as if for many hundreds of years they didn’t, which is important to consider. And yet, they seem to have been able to train quite fine without serious injury. Remember that these were commonly craftsmen who relied on their eyes and hands to survive. Hitting them by accident was strictly forbidden and had severe consequences. I think we are quite capable of reaching that level also, with time and hard work.

But, everyone dropping all gear and fighting hard with steel would be insane. It is not what I am suggesting. Instead I propose that we work with a variety of approaches that aim to infer this mentality into people, approaches that suit different weapons and skill level and experience in different degrees. So when I mention “minimal protection” this is not a single specific kit and can mean wearing a variety of gear, with or without mask. And some of the examples I give are actually meant for full kit, like the ones with restricted or instant-kill targets.

Your fear that limited targets will move you away from the original teachings I think is invalid, as I am not suggesting it as the ONLY approach, but just another type of exercise that help you become more dynamic.

I often hear such criticism against restricted exercises and I think that is a complete misunderstanding. For example the flow exercise we have worked with with no thrusting and often not even including footwork has had an instant effect on people who have trained with me, with them noting that they improved right away in their sparring. Dynamics is the key word here, which is also why I don’t see issues with restrictions in tournaments.Some restrictions can actually make us more dynamic and better fencers, as long as we acknowledge that we need to work with many different approaches that all encourage the use of the Art with a correct mindset.

And for sure, we must keep on fencing with all our gear too. I never claimed otherwise, but we need to learn to not rely on it to keep ourselves safe. Some fighters already know how to do this quite well.

I only have six years of HEMA study but my experience disagrees with everything you’ve said. In all that time, training primarily with only gloves, mask and a sword (don’t forget that the weapon is the best protective device), the worst injury I’ve sustained is a losing a thumbnail in a poorly executed parry. That incident went further than any drill to correct my technique.

If we need to armor up to practice “blossfechten” we’re obviously doing something wrong, don’t you think?

Thank you for sharing these thought and process. I will re read and digest them for some time.

A very good article, Roger. Thanks for posting it. Understanding the context in which the treatises were written is a particular concern of mine and you’ll find me stepping up onto that soapbox every chance I get.

It puzzles me, though, that the issue needs to be spelled out like is. Surely, it’s not just the Australian College of Arms which trains in this manner, sparring with and without protection. For us, this reflects our emphasis on respecting the weapon and what is/was originally designed to do.

The first rule of fencing is and was always “don’t get hit.”

Thanks Chris!

Yes, many people train and spar with little protection, but doing various forms of exercises that actually put some proper fear of getting hit isn’t as common I think. This means to under controlled forms dropping all gear, when you are ready for it and with a partner you trust. It really heightens your awareness and that is what I am really after. It is something we need to transfer to fencing WITH gear too.

It is also a bit of a generation shift I think, with new fencers who start with everything in place. Nowadays there is a lot of good HEMA-specific gear available already and you don’t even have to study the original sources as there are quite a few good instructors that can teach you. Me, I think we all need to think for ourselves, and debate regularly, to learn how all of this connects. I believe we have a couple of decades until we will have proper and good understanding of what we study.

“One of the most important aspects to research other than just reading the instructions in the treatises, is to study the context in which they were written and designed for. For this reason we need to study all aspects of the medieval and Renaissance society”

– That is right, Roger. It is wonder how could two people in so large distance think about one thing and in the same direction. May be it means that people goes in the right deirection investigating HEMA. 🙂

I wrote in conclusions at the section “About HEMA” at http://www.onfencing.com comparing Russian historical fencing and europian HEMA as it:

“If you talk about HEMA, it is inherently HEMA can be compared with the Eastern martial arts which have always been inextricably linked to the culture and philosophy of the people, their practitioner. HEMA “says”: “To understand the martial arts of Europe, it is necessary to study the culture, philosophy and traditions of the peoples who inhabited Europe” […]

“I would like to say a few words about the importance of the original source – the treatise, fechtbuch, textbook – without which there would be no HEMA. In modern terms of management, any textbook on fencing – this is primarily the result of the authors’ estimation of their potential Target Audience. “I know who you are and what you need, because I am part of you.” We do not know exactly how many people have been practicing his technique and how much. But we do know that there are certain objective preconditions for appearance of this technique, in this Target Group. Thus, we obtain information on trends in the social culture of the Target Audience. That is, the technique is not for the sake of the methodology as it may seem at first glance, but as the author’s subjective response to the objective needs of the Target Group.” […]

“HEMA is based primarily on methodological study of the source, and only then it is an attempt to test the practical effectiveness, depending on external conditions: workshops, freeplays or tournament activity.”

Thank you, Roger, for good article!

I liked this article a great deal. Perhaps though like the last half did not seem needed or to make sense however, what with some of those ugly videos. That said, its merits are high, and you speak of things that tend to bring forth ape-rage at some forums, e.g. “all aspects”. Especially to speak of things Chivalric. Thank you.

Thanks Jeffrey! Glad to hear it! I would love to hear you expand on why you don’t think the last part fits with the rest. I assume you refer to the Calinda clips. Personally, I think we can learn quite a bit from studying them.

Down here in Tasmania the two schools we have (Stoccata School of Defence & Historical European Fighting Tasmania) both seem to follow this idea! Ha! Granted it may be because shipping anything down this way doubles the cost; but it’s nice to see that, at least in one type of practice, you don’t need a whole bunch of kit just to have a fair go.

Hi Sam!

It is always interesting to hear from people around the world how they approach their training. Note however, that I am not suggesting one should only practice with little or minimal protection. I am speaking of a varity of approaches and methods, but all of them based in a mindset coming from not wearing any. However, there are traps with wearing little protection also, usually with people avoiding certain things for fear of injuring their friends.

Here is a response I wrote on another forum:

“It is always interesting to hear from people around the world…”

Ditto. 🙂

Sorry, I should have been clearer. What I meant by “… at least in one type of practice…” was that we use a variety of methods (including the aforesaid) with varying levels of equipment in relation to what we want to achieve in that particular practice.

Anyway, excellent website! I check it almost daily and it’s certainly given me lots to think about. I hope that I might be able to contribute to it eventually; maybe something to do with pikes…

Regards,

S.

Easily the most important HEMA articles in many years.

I agree with you completely Roger.

After years of training with al our gear, we took the step to gradually dump our protective gear. Now we are on the point of using only our masks.

The effect was overwhelming. For the first time in years I was able to use right Och’s and schrankhut’s. For years my gear limited these postures/my technique.

Like you said, it shifts your mind in a completely different mode. You are VERY aware of what’s happening and what safe options you have.

The only downside is your partner. He or she has to be in the same mindset. You can’t do this with everyone.

Love the article

Roger,

This and your Laurel Wreath article really are a magnum opus! I am not sure if you sleep anymore, my friend, but if not, please keep staying up all night – it may not be good for your health, but it’s great for discussion of our art!

Of particular note is this:

” I wish to, as much as possible in our modern day, understand what the masters of old are trying to teach us, to understand how the fighting arts were performed with regards to techniques, tactics, strategics, limitations based on practical realities with regards to concepts of honour, manliness, fairness, practicality and so on. ”

This is worthy of a tattoo! (I nominate Mike Cartier’s body for this.) Seriously, you sum up nicely the purpose, IMO, of studying any traditional/historical fighting art, rather than a modern combat sport or simply modern self-defense combatives. Sadly, although I increasingly disagree that “this is what most HEMA practitioners seek to do”, I think it is what most folks claim that they seek to do and it is what we *should* seek to do and *must* seek to do if we want to maintain the “H” in HEMA.

Anyway, great work!

Greg

Thank you my friend! I really appreciate your comments!

I am not so sure I would extend that paragraph as far as you do here, as there can be many different motivations for both approaches. I am simply stating my personal ambitions, ambitions that I know many share. But, if you share these ambitions in wishing to understand the teachings of the masters as deeply as possible, then I sincerely believe it is very, very important to study the context from as many angles as possible.

This does not mean that we should create some form of modern chivalry etc, which I know some fear, but rather that we need to try to understand the mindset, the purpose and various limitations that were in play here. Without it, we will still have good, modern HEMA, but this is not what I personally am after. I wish to go deeper than just being a good fighter in a general sense, not least since such a thing is really hard to define at this stage of HEMA, as it depends very much on how you choose to measure it. Still so much work left to do that I can only hope to see us get near a deep understanding within my lifetime.

As I’ve said elsewhere, there are many ways that one can take HEMA, but there are differing levels of “H” you get, depending on your focus. A martial art divorced from its historical, social and philosophical context may be perfectly good “fighting”, but it is not the same art – it seeks to be something traditional or historical. We see this in Asian arts a fair bit, but it is much more of a danger in HEMA where there are no living traditions and many of the people researching or reconstructing a) don’t read the original languages, b) have very little understanding of how historiography works, c) don’t know much about the general history of the period or d) are interested in a very narrow focus.

You simply can’t say “well, I study 15th c German longsword”; I don’t need to know about wrestling or armoured combat; I don’t need to know about Scholasticism or what was going on historically. I just have to do what the book says.” That just isn’t how books coming into being, let alone martial arts. You don’t need to be an historian, but you at least need a general overview and understanding of how medieval books were produced, what the process of auctor and commentary was, and what the role of knighthood, judicial duels and weapon use were in the HRE. (A lot of mistakes would be avoided if people just knew what the word “naked” meant contextually to a medieval audience!)

The more you move away from that or ignore it, the more misunderstanding can arise, particularly in mindset. As you add gear that is different from historical gear, behaves differently and causes combatants to move differently, you add a second distortion. Once you remove fear – the thrust of this article – you then run the risk of creating an environment where the techniques and actions that get the most use are not necessarily the ones most advised by the masters themselves. People strike too fast, too hard, and get in too close, etc., as you’ve outlined.

Now, I am decidedly in the traditionalist camp – after years and years of sport combat, for me, I study HEMA for the same reasons I have a history degree or studied koryu martial arts: for both the training and the understanding of a culture that was the predecessor of my own. That puts me at odds with a lot of the more “modernist” practitioners, and that’s OK. I actually don’t even mind the hard core “sport sword” crowd, I just think they need to understand that what they want will and *must* take them away from *H*EMA, just as it has with other combat sports. Just the nature of the beast. Kit up, pick up your nylon weapons, hit the tournament circuit and have a good time. But *accept* that, and don’t mistake any simulated sparring for real combat.

Now I know where you get your footwork.

Hi Jay!

Yes, I have studied Jogo do Pau quite a bit since I believe it is very close to Meyer’s fencing style. Just compare this image of Luis Preto and Nuno Russo:

And when you read his stucken, the similarities are quite obvious. 🙂

Great meeting you btw and I really enjoyed the short bits of sparring we got to do! Not to mention your great class!